I never met a bookshop I didn’t like. I particularly love the quirky ones, with nooks and crannies, comfy chairs, tables, mirrors, the occasional dog. Those dispensing coffee get double stars.

I”m talking about real bookshops. Not those totally online international hussies that parade their wares like ladies of the night, and are basically committed not to literature but to making money.

Sure, real bookshops are businesses too, and they need to survive financially, but when you walk through their doors you can feel an ambience, inhale a bookish ‘smell’, that no online purveyor can hope to replicate.

This is especially true of independent bookstores, where the owner is often behind the counter. I’m not bagging the franchised chains here (I shop there too, and know they have dedicated staff), just admiring the gritty guts of those bookshop people who choose to do it for a living (or not).

Whenever I travel, I look for independent bookstores and usually buy a book to celebrate my visit, a tiny contribution to fostering their continued success. Every one of them is different, but they share a common feel of compressed creativity, a colourful pandora’s box of treasures waiting to be discovered.

They usually have a dedicated following too. In July 2025, the 103-year-old Hill of Content bookshop in Melbourne’s CBD recruited hundreds of volunteers in a human chain to transfer their stock of 17,000 books to a new location nearby after their building was sold.

Depending on your tastes, there might also be some occasional dross, where the contents don’t live up to the back-cover hype, but it can still be fun looking. Besides, as a writer I admire anyone who’s managed to convince both a publisher and a bookseller that someone might want to read what they’ve sweated over for so long.

For me the appeal of the ‘real’ bookshop over the online one is the chance to pull out a book from the shelf, read the cover blurb, flick through the pages, check the font size, feel the texture of the book between my fingers. Even the weight of a book tells me something. Then I might clasp it as a ‘possible’ while continuing to wander the shelves, hoping I can remember where it came from if I decide to put it back.

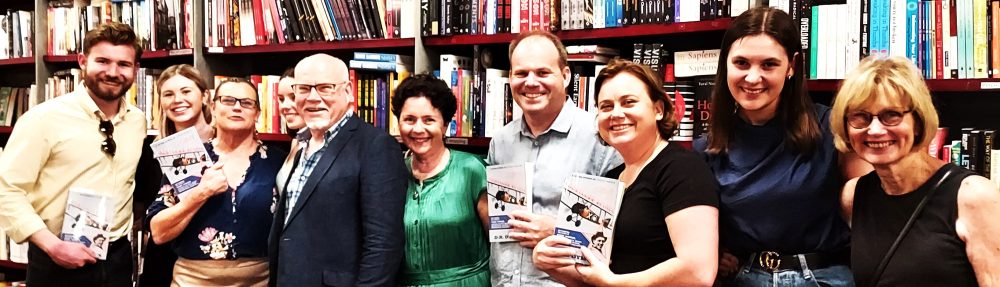

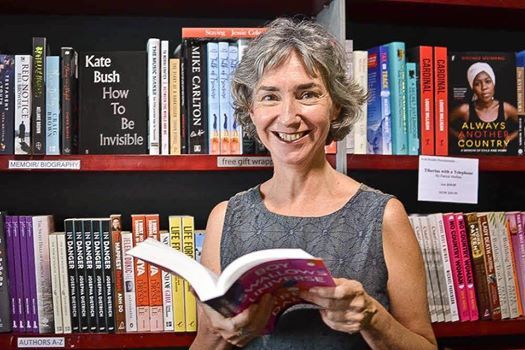

In 2020, in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, I recorded four interviews for an invited blog for Margaret River Press, Western Australia. It was a tough time for booksellers, and Fiona Stager, co-owner of Avid Reader Bookshop in Brisbane’s West End, told me in May that year, ‘If we have a good Christmas, we will all make it.’

Five years later Avid Reader is not only still going strong, but Fiona and her partner have taken over Riverbend Books in Bulimba, on the other side of Brisbane.

I have a particular affection for both bookshops, because they hosted three of my book launches: Hustling Hinkler (2013) at Riverbend, and The Chalkies (2016) and A Great and Restless Spirit (2022) at Avid Reader.

Riverbend Books was formerly owned by another stalwart of the Brisbane literary scene, Suzy Wilson. She and Fiona are long-time supporters of the Indigenous Literacy Foundation, whose programs focus on instilling a love of reading at an early age in some 400 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander remote communities across Australia.

Both stores not only sponsor book launches, but also author talks, ‘crafternoons’, trivia nights, book clubs and various other literary events that take ‘reader engagement’ to a new level. Avid Reader has a spin-off store next door for younger readers: Where the Wild Things Are, a name taken from the outrageously successful children’s book by Maurice Sendak.

Despite my passion for ‘real’ bookshops, as both a writer and reader of books I’m grateful that there are digital options available for authors to publish and readers to access books. According to a recent article in the Sydney Morning Herald ‘Weekend Magazine’, more than half of Australians aged between 15 and 34 read e-books and almost one in three Australians listen to audiobooks.[1]

A younger friend of mine recently returned a non-fiction book I’d lent her (not one I’d written), apologising that she was out of practice with hard copy because she was used to ‘reading’ via an online app and a set of headphones.

I’m thankful that we still have in Australia what publishing agent Jane Novak called (in that same SMH article ) ‘a very healthy bookshop ecosystem’ (including second-hand bookstores, a genre in themselves). ‘Plenty of people thought e-books were bad for book sales,’ she said, ‘but they haven’t impacted the sales of hard-cover books in the way we thought.’

Let’s hope the market can continue to support independent bookshops like Avid Reader and Riverbend Books, not only because they provide a hands-on experience for readers, but also because they help sustain the culture of thriving local communities.

[1] Greg Callaghan, ‘The final chapter?’, SMH Weekend Magazine, 5 July, 2025, pp. 9-11.

was ‘Alas, poor Yorick. I knew him, Horatio – a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy.’

was ‘Alas, poor Yorick. I knew him, Horatio – a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy.’ as he did, he would no longer be crazy and would have to fly more missions. Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he was sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t want to he was sane and had to. Yossarian was moved very deeply by the absolute simplicity of this clause of Catch-22 and let out a respectful whistle.

as he did, he would no longer be crazy and would have to fly more missions. Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he was sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t want to he was sane and had to. Yossarian was moved very deeply by the absolute simplicity of this clause of Catch-22 and let out a respectful whistle.

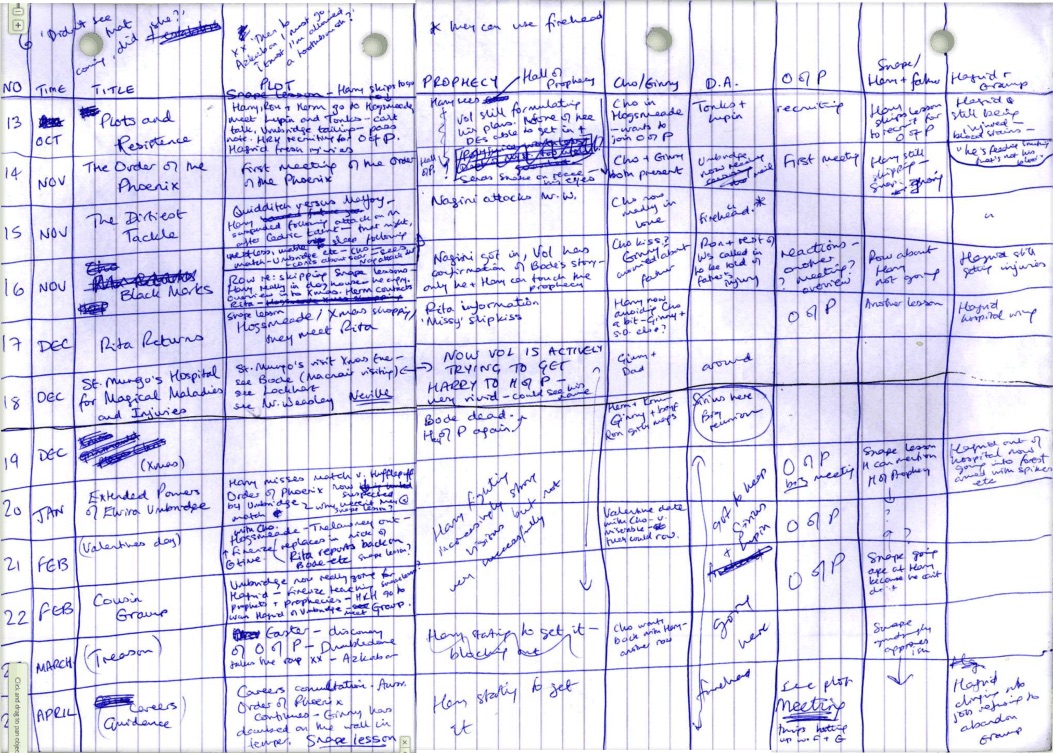

I understand J K Rowling writes her novels by hand first. I wonder if she feels relief from anxiety, fear and worry when she’s finished? Richer in some way, at any rate 🙂

I understand J K Rowling writes her novels by hand first. I wonder if she feels relief from anxiety, fear and worry when she’s finished? Richer in some way, at any rate 🙂 The American novelist Ernest Hemingway (often called ‘Papa’ by those who knew him) once said he wrote thirty different endings to A farewell to arms. He told this to a distinguished Australian journalist and war correspondent, Alan Moorehead, when the two met in Italy in 1949.

The American novelist Ernest Hemingway (often called ‘Papa’ by those who knew him) once said he wrote thirty different endings to A farewell to arms. He told this to a distinguished Australian journalist and war correspondent, Alan Moorehead, when the two met in Italy in 1949.

In a recent critique of Hemingway’s writing (Yale University Press, 2015), the Australian-born author and literary critic, Clive James, praised the American’s early novels but suggested that Hemingway’s later work was ‘ruined’. James said that Hemingway, ‘having noticed how the narrative charm of a seemingly objective style would put a gloss on reality automatically, he habitually stood on the accelerator instead of the brake. … He overstated even the understatements.’

In a recent critique of Hemingway’s writing (Yale University Press, 2015), the Australian-born author and literary critic, Clive James, praised the American’s early novels but suggested that Hemingway’s later work was ‘ruined’. James said that Hemingway, ‘having noticed how the narrative charm of a seemingly objective style would put a gloss on reality automatically, he habitually stood on the accelerator instead of the brake. … He overstated even the understatements.’ author

author

image, scene, or voice. Something fairly small. Sometimes that seed is contained in a poem I’ve already written. The structure or design gets worked out in the course of the writing. I couldn’t write the other way round, with structure first. It would be too much like paint-by-numbers.’

image, scene, or voice. Something fairly small. Sometimes that seed is contained in a poem I’ve already written. The structure or design gets worked out in the course of the writing. I couldn’t write the other way round, with structure first. It would be too much like paint-by-numbers.’ ‘I’m cursed with not being able to see the good twists and turns of character and plot until I’m in the middle of writing the book. I can have a sense where it’s going, but absolutely nothing comes alive until the words start going down on the page. ~ Romance author Jane Graves.

‘I’m cursed with not being able to see the good twists and turns of character and plot until I’m in the middle of writing the book. I can have a sense where it’s going, but absolutely nothing comes alive until the words start going down on the page. ~ Romance author Jane Graves.